The focus of my time here in Japan is on a giant, coldwater fish that is only found in Asia … the group of fishes (there are five species) are known as taimen (“tie-men”, or if you are American “tay-men”) or huchen (“hoo-kin”, unless you are American, and you pronounce the “ch” like it is pronounced in “choo-choo” train!). I learned about them first in a lecture by Dr. Neil Ringler when I was a young, impressionable graduate student at State University of New York in 1987. I remember him scrawling out that strange word Hucho on the blackboard, and how he described it as a true giant, the largest of the salmonids (the taxonomic group that reign supreme in cold water rivers and lakes in the northern hemisphere). It definitely caught my attention and imagination at the time (since a very early age, I’ve always been drawn to fish and rivers), but any in-depth thought on this particular group of fishes, or their place in the world, lay dormant for many years.

Fast forward to 2003, when I was hired as a new staff member at a small conservation organization called the Wild Salmon Center in Portland, Oregon. Within the first week there, I found myself at a table with Xanthippe Augerot, staring at an impressively tall stack of documents that she hoisted to the center table. She and Guido Rahr, the president of the Wild Salmon Center, had just created a new “specialist group” for salmonids within IUCN (the International Union for the Conservation of Nature) with the help of Russ Mittermeier, the President of Conservation International. Xan and I talked about the potential role of this international group, and our conversation slowly got grounded in what was practical and doable. During that conversation, she mentioned this species to me, Sakhalin taimen, and it struck a chord as I thought back to my early graduate school training. During that conversation she spread out all the ingredients for a very intriguing and rewarding intellectual journey, embedded within a very important cause – protecting a giant salmonid in a far-away, exotic place. I had spent the last 10 years working in British Columbia, North Carolina, Alaska, the Bahamas and few other places, but Asia was on a whole different level! And while my training and background had been largely on research to improve the way we manage fisheries, the species conservation dimension of this particular problem greatly intrigued me. My plan quickly took shape – pull together all the specialists and relevant data on the species and summarize its current status in the wild. As part of that, lay out priority river conservation actions and get new, important research underway.

Since then I have been growing a network of colleagues around the world that have a deep, enduring curiosity and concern about these fishes, and they all bring unique talents and perspectives to the table. I certainly bow in regard to similar research and conservation groups working on various charismatic flora and fauna (and fungi, even!) in far flung locations on the earth, but there is something really special about these fishes, at the risk of landing on a cliché. They cut across all sorts of intriguing issues and geography, and there is more there than any one person could tackle in a few lifetimes. For me, I’m just trying to make the best go of it, particularly challenging for a person that is not particularly outgoing by nature. At the end of the day, I am hoping to leave some lasting legacy involving salmon and rivers.

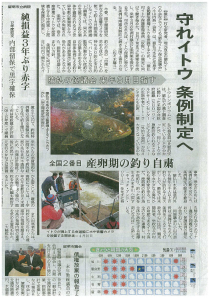

So here I find myself in a small village in the extreme north of Japan. The village is more like what we would call a rural county in the US. It is very thinly populated (just over 2,000 people), and dairy farming, fishing and some logging supports a large part of the economy. I first came here in 2006, and I have made a number of trips since then. This year is different, though, as I start a new field project that demands a greater investment in time, coordination and communication. The main objective of the project is pretty simple in theory (in practice, well it is a bit more complicated, as you’ll see later!): to estimate the number of endangered itou in a major tributary of the Sarufutsu River, one of the best preserved “wild salmon rivers” left in Japan. That is not much of an exaggeration, actually, as most rivers, like many rivers around the world, have been greatly modified to “bend the will” of the river to the needs of humans. This includes a whole host of things, including daming, dyking, water extraction, gravel mining, channel straightening, etc. In this part of Japan, it is mostly about accommodating agricultural land, controlling erosion, and providing drinking water.

The Sarufutsu River, however, largely escaped this fate, and today can really be described as an untamed, wild river. This is rare, indeed, in a country as developed as Japan. This river was named “river of the reedy plain” by the Ainu, the native people of this region. To this day, the name is apt, given that there remains intact, natural floodplain and wetlands that provide important habitat for wildlife and serves the regional community in many ways, perhaps not always fully appreciated. This river is not only a productive salmon river, but it is just awe inspiring and beautiful. From its mountain headwaters, if flows through valleys with what stream people call “highly sinuous channels”, where the stream bends around on itself, so in many places you can be standing between two channels just meters apart and the rivers will be flowing in opposite directions. I am not a Buddhist, but this is one of those places I can feel enlightened! The forests in the headwaters are diverse, with a mix of fir and broadleaf deciduous trees, with particularly striking birch tree groves and very large Mongolian oaks in the floodplain. The understory makes these rivers appear very different from the ones I am familiar with in the U.S. The dominant plant (and I mean dominant, it is everywhere) is sasa, a small bamboo plant. The annual routine with this plant is to get completely flattened by snow during the winter, and then, as the snow melts away, straighten and grow to a height of about 10 feet during the summer growing season. It is the dominant riparian vegetation (the strip of plants that line and stabilize river banks). I think the plant is very cool, but I also consider it my nemesis, as I will need to navigate through it (many, many kilometers) as I work in the river. Anyway, more about my travails with sasa later in this blog!

The river continues on to a broad, flat plain, with a mix of wetlands and agricultural land. The channels are deep and the current is slow. A large lagoon exists near the mouth. The last 5 km of lower river has been straightened, but, all in all, the wild character of the river remains intact. The river flows into the Sea of Okhotsk (quite possibly the most difficult pronunciation exercise ever devised by humans … don’t even try it!). Anyway, itou spend a part of their life out in these frigid coastal waters.

So, that is itou, and the lucky ones can call the Sarufutsu River their home.